This is the last part in a series on basic principles of design. We made it! Check out the intro, part 2, part 3, part 4, and part 5 if you haven’t already, then get ready to dive into today’s topics: prospect/refuge, panorama, vista, and deflected vista. These final four principles are a bit more conceptual than most of the others we’ve discussed, but once we understand them, we’ll be equipped with all the necessary vocabulary to effectively study and discuss designed spaces!

Prospect/Refuge

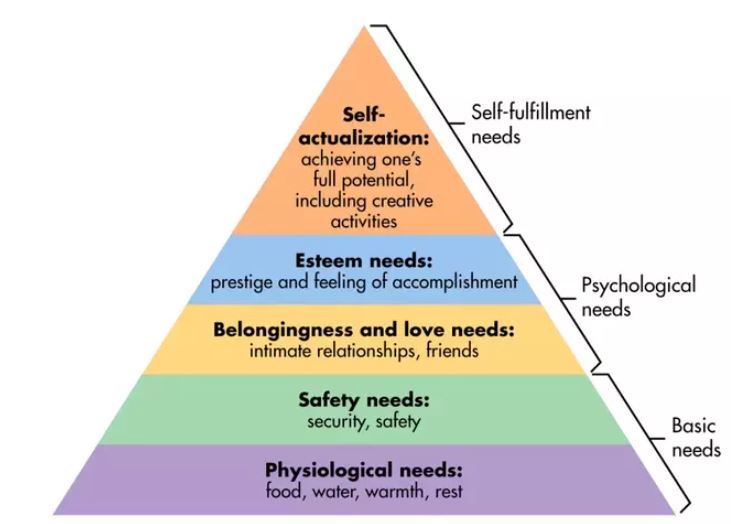

This concept is quite abstract, but it is very important. The idea of prospect/refuge appeals to our basic human need to feel safe. In Maslow’s Hierarchy of Needs, safety and security are among the most basic human needs, only after basic physiological needs like food, water, and shelter.

In the most basic terms, “prospect” describes looking, and “refuge” describes the feeling of being sheltered. Think about the last time you were people-watching. Maybe you didn’t have a choice where you could sit, but if you did, I’d bet you chose a spot towards the edge of the area you were watching. An abundance of research has been conducted on the theory of prospect/refuge, and (good) designers consider this innate human need when trying to make comfortable spaces. The next time you’re in a public space, look at what seats are occupied and which are empty. It is most likely that the edges of the space, where people can observe while feeling protected, fill in much quicker than more exposed, central spaces.

Prospect/refuge relates heavily to many of the topics we have discussed throughout this series. For example, being “below” as opposed to “above” makes it easier to feel safe, with your back protected by the slope. Scale also relates to the feeling of safety, with it being much easier to feel safe in a smaller space. In larger spaces, prospect/refuge must be designed more intentionally.

Panorama

The final three principles deal with views. The first, panorama, describes a wide view. We all know what a panoramic view looks like; whether it be a waterfront, a mountaintop, or a simple clearing on a hill, we’ve all seen a larger-than-life view that takes our breath away. In design, it’s important to respect such a valuable feature. When you’re given a space with an amazing view, it is your responsibility as a designer to do justice to the view, attractively framing it rather than blocking it out with unnecessary obstructions.

Vista

A vista is a type of view that is more restricted than a panorama. It still includes an attractive and deep field of sight, but foreground features focus the view through a smaller window than is available when viewing a panorama. Incorporating a flowering tree or another framing feature compliments a vista nicely. Obviously, since the view of a vista is already partially obscured by the foreground, designers must be careful to avoid blocking any more of the precious view. Additionally, distracting focal points in the foreground and midground may detract from the view. Instead, care should be taken to direct the eye out towards the vista.

Deflected Vista

When I first learned about deflected vistas, I thought the terminology was a bit weird. If a vista is a narrowly framed view, then what is the deflected version? As it turns out, a deflected vista is one where most or all of a view is obscured or hidden around a curve. A deflected vista makes you pause and think “huh, I wonder what’s around that corner”. Cultivating this mysterious atmosphere can be difficult to achieve, but when you successfully guide someone in this way, the payoff is huge. Imagine a hike where you’re reaching the top of the hill, but the trees are too dense to see what’s around you. You reach the top, round a corner, and suddenly you’re met with an amazing view over the surrounding valleys. The sudden, unexpected view is more memorable than one you can see glimpses of throughout the whole hike.

In a smaller context more relatable to residential design, the importance of a deflected vista is its ability to cultivate a sense of mystery. A subtle curve that obscures what’s beyond inherently sparks our curiosity. The curve also provides refuge for those beyond it, contributing to the ability to create prospect/refuge.

Conclusion

Thanks so much for tuning in over the past six weeks to learn about basic principles of design! I hope that you feel better equipped to actively engage with the world around you, prepared with the vocabulary to describe what you see. When you really stop to look around, you can gain so much more appreciation for your surroundings than you previously had. When I first learned these design principles, I began to see the world around me totally differently. Even places I had seen a hundred times before gained a new meaning, and I felt more connected to the things I was seeing, and the people who designed them that way.

Good information, really helpful for independent studying as a landscape architecture student.

awesome, good luck with your studies!