One of my favorite things to do on this blog is to profile recent projects. It's a fun opportunity to show what's possible, and maybe brag a …

Landscape Installation

What Concrete Paver Goes with My Brick House?

I get asked that question a lot, as you can imagine. After all, Virginians love their brick homes, so I design a lot of patios for brick …

Building a timber wall – will it last?

I like to play a game I call underrated/overrated. You can play it with bands, actors, foods, anything you want. Example: …

Space Planning to Make a Beautiful Vienna Virginia Backyard Better

I'm often called in to make an existing landscape function better. The client doesn't to rip it all out and start from scratch, but they …

Travertine Paver Patio Installers in Virginia – What to Know

When I was designing landscapes in Arizona, one option we had available to us was travertine marble tile. These were actual tiles - …

The Importance of Compaction for Installing a Paver Driveway

On behalf of a contractor client I'm working with a great couple who are building a new custom home in northern Virginia. As part of the …

Understanding Flagstone: Sawcut, Thermaled, and Chiseled Edges

You've decided to use flagstone in the landscape. Good call! You may not be done making decisions, however. If the stone will be used in an …

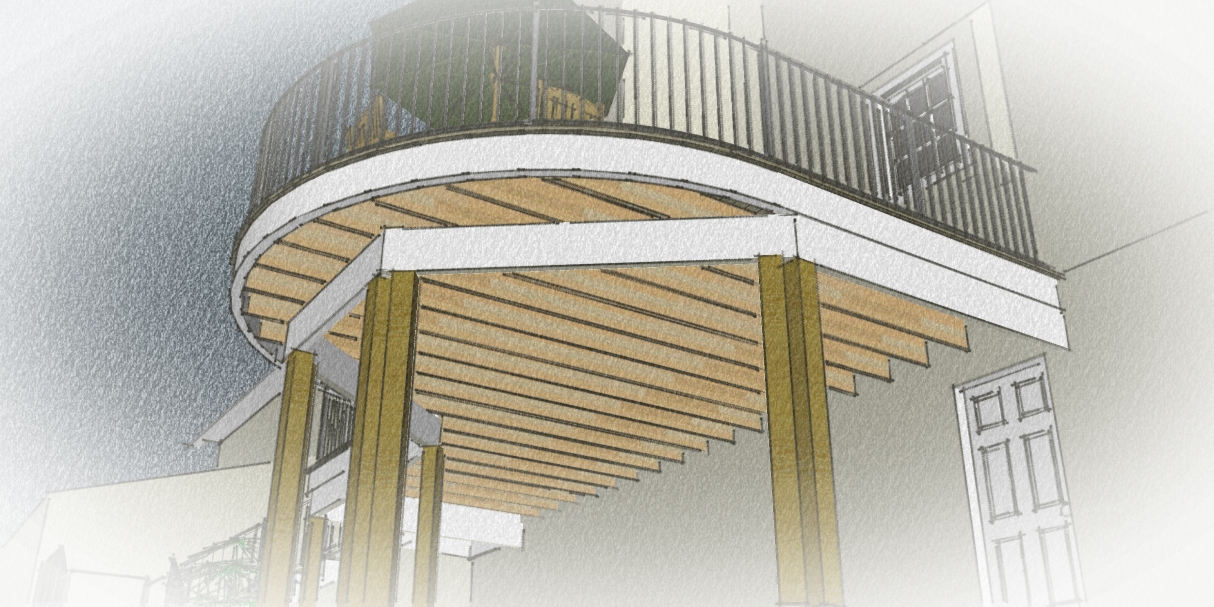

Virginia Deck Design Explained, Part 2: Posts, Beams and Joists

Last week I talked about the ledger board and the footers, the first steps in building your deck. Today I'll cover the next …

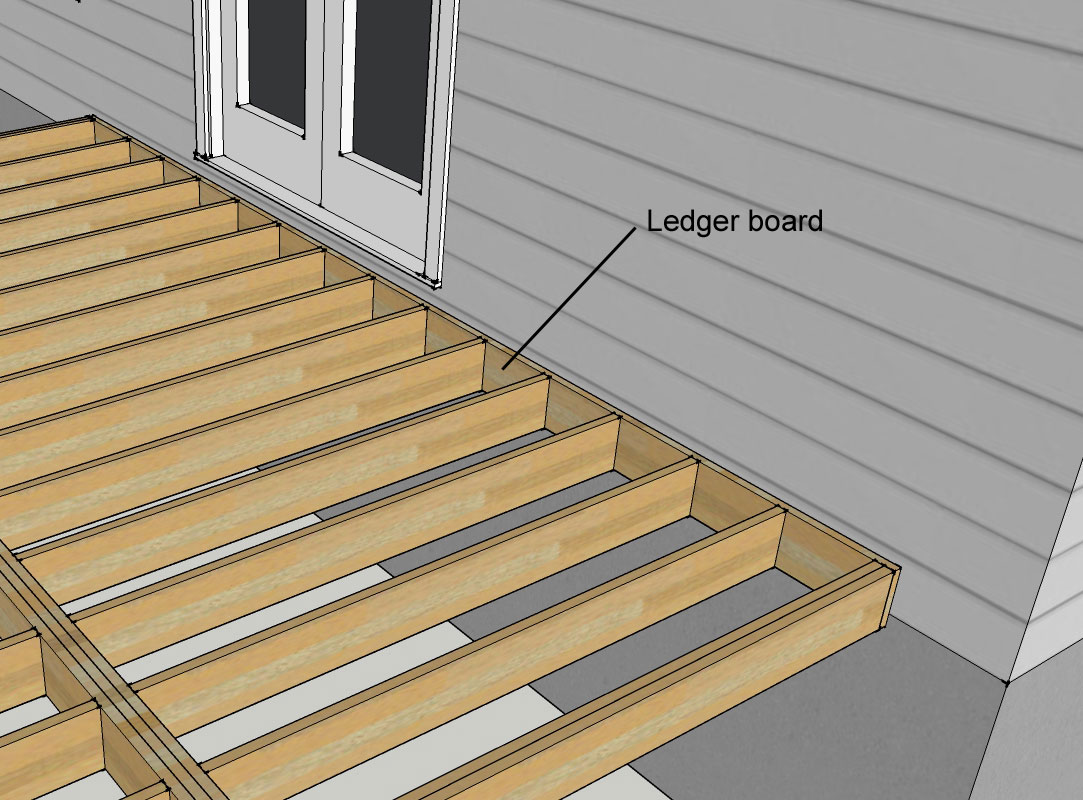

Virginia Deck Design Explained, Part 1: Footers and Ledger Attachment

My name is Dave Marciniak, landscape designer and owner of Revolutionary Gardens, and I use jargon. I'm deeply sorry. However, the …