Since I was young, my parents have always been big advocates of traveling. When I was 5 years old, for example, my dad had to take a business trip to France. He decided to turn it into a family vacation. It was February, and I was allowed to drink all the hot chocolate I wanted under one condition: I had to order it myself, in French. They taught me to say “Je voudrais chocolat chaud, s’il vous plaît” and trust me, I took advantage of that any time we sat down at a restaurant or passed a street vendor. Their perspective towards travel as not just a leisurely pursuit but also an opportunity to learn persists today, and it had a huge influence on me.

When I chose to attend Penn State for landscape architecture, the program’s pitch included many chances to go abroad. If you haven’t read my first post on studying landscape architecture at Penn State, there are more details there! During my third year, I elected to spend the summer in Barcelona, Spain along with about half of my classmates. Penn State has a relationship with a small school based in Barcelona called the Barcelona Architecture Center, or BAC. The BAC works with numerous universities, bringing students from schools across the US to study throughout the year. Penn State’s program specifically is a 6 week intensive program, held every summer.

Landscape design: Two approaches

Before I go into the details of my experience in Barcelona with the BAC, I’d first like to explain a bit of the difference in philosophy between the US and Europe in terms of landscape design. In the US, landscape architecture is a recognized profession, where people such as myself learn about a variety of topics, ranging from design and planning to planting and climate. To call yourself a “landscape architect,” you must take and pass official licensure exams that contain both general knowledge and information specific to the region where you are being licensed. For example, flood-prone states may include a section on floods in their exam, while northern states may have a specific section dedicated to designing for the freeze-thaw cycles of northern soils. This approach makes American-educated landscape architects more generalists than specialists: we can talk to contractors about our technical drawings or botanists about plants, but we aren’t typically experts in any one subject. That is, of course, unless we choose to pursue additional degrees in your area of interest (which many landscape architects do).

In Spain, as with much of Europe, “landscape architecture” isn’t really a thing. Most landscapes are designed, layout-wise, by architects, with the help of plant specialists and others who may have a better understanding of elements an architect hasn’t learned. Many landscape architects in the US have a negative perception of architect-designed landscapes. Some believe that without training regarding plants, architects treat plants like any old inanimate feature, scattering them around to “make it look pretty.” Parts of this criticism are true: architects aren’t taught about biodiversity, benefits of planting native species, or the sunlight or water requirements of specific plant species like landscape architects are. This can lead to a less informed approach to planting design that doesn’t fully take advantage of the amazing palette of plants with which designers have the opportunity to work.

In the European system, though, these considerations are undertaken by experts in those fields, who apply their knowledge to a layout planned by an architect. Obviously, architects are highly qualified in terms of spatial organization and layout design. While I obviously don’t have experience working in this kind of system, I can still see how there could be issues when splitting up this work between multiple people. In my opinion, there isn’t one “better” way to do it, although I am obviously biased towards thinking my education and particular skillset are beneficial to the design world.

Arrival

When I arrived in Barcelona, I had never traveled internationally by myself before. I didn’t know any Spanish beyond the VERY basics, and the only instruction I had was where to catch the bus from the airport to the center of the city, and how to get to my dorm from the bus drop-off. It was hot, and I was sweating as I disembarked the bus in Plaça de Catalunya, dragging my suitcase laboriously down the bumpy cobblestone sidewalks of La Rambla, but I was excited for the adventure ahead of me. Once I was moved into my room, I met up with some of my classmates and we got accustomed to the neighborhood that would be our home for the next six weeks, exploring the nearby shops, cafes, and bars.

Our second day there, we had a welcome party at our professor’s office. Located in the Eixample area of the city (more on Barcelona geography later), the office was converted from a 150 year old home into a beautiful workspace. Our party took place on the lush, expansive patio located in the courtyard of the block. Neighbors on their balconies overlooking the courtyard played music and hung laundry out to dry. While I knew that I would have a lot of work to do and a lot to learn, this relaxing introduction to life in Barcelona encouraged me that the experience along the way would definitely be unforgettable.

When our classes began, we followed a mostly regular schedule, with trips and activities built in. Most class days we were in the BAC studio for at least 8 hours. We had history lessons once or twice a week and spent much of the rest of the time learning about our studio site and developing our studio projects. We had a series of walking tours of Barcelona landmarks, and once a week we would take a day-long field trip to another Catalan city to gain perspective on the wider context of Catalan design, culture, and experience.

History

The history of Barcelona is very interesting, and the lessons we got always enriched my experience while walking around observing the city around me. Most of the Old City of Barcelona is actually built directly on top of the ancient city. The neighborhoods of El Raval, Barri Gothic, El Born, and La Barceloneta compose the Ciutat Vella (or the Old City). In 1859, Ildefons Cerdà developed the plan for the expansion of the city, following his theories of urbanization. The Cerdà plan sought to address issues posed by the structure of the Old City. Since until that point the city grew quite organically, its roads were narrow, winding, and confusing. This resulted in a dense labyrinth where many of the city’s inhabitants lacked access to public services and often even sunlight.

The Cerdà plan proposed an expansion radically different from the existing urban fabric. The expansion, or “Eixample” neighborhood, consists of wide streets laid out in a highly legible grid. Each block’s corners are cut, or chamfered, at a 45 degree angle. This further opens the intersections to receive plenty of sunlight and enhance visibility around corners. Each block also is designed with an interior courtyard, like the one where our welcome reception was held. The Ciutat Vella and Eixample are easy to differentiate on maps, like the one below, thanks to their extremely different structures. Notice also that Eixample connected the city to surrounding municipalities like Gràcia, incorporating them into the city of Barcelona. You can tell that these areas are older than Eixample by their fine-grained structure, more similar to the Ciutat Vella than the newer Eixample.

Since 1859, a lot has happened and changed in the city. The Parc de la Ciutadella was designed for the 1888 World’s Fair. Many aesthetic improvements were made to the city in advance of this major global event. Unfortunately, other changes that have transpired since this time include the infill of most of the courtyards of Eixample to accommodate increased population and the introduction of cars into the city. In recent years, “urban voiding” has sought to restore some of these spaces, but the full potential of these areas as green oases still remains unrealized.

Antoni Gaudí

Of course, any discussion on Barcelona, especially from a design perspective, would be incomplete without mentioning Antoni Gaudí. Our curriculum took us on tours of many of the Catalan Modernist’s most famous works. These include Casa Batlló, Park Güell, Casa Milà, and of course, La Basílica de la Sagrada Familia.

Casa Batlló

Park Güell

Casa Milà

La Basílica de la Sagrada Familia

Gaudí took inspiration from nature, rejecting the straight lines of more traditional styles of architecture in favor of more natural shapes. Gaudí’s designs mimic the gentle, imperfect curves of trees, landforms, and even structures of the human body, like our bones. He practiced during a time of “rebel architecture,” where Catalan architects dotted the landscape with daring works that embraced the free and independent spirit of the Catalan identity. One striking example of this period of architecture is the so-called “Block of Discord.” Located on the luxurious Passeig de Gràcia in Barcelona, this block is home to many revolutionary works of architecture, the three most notable of which are Lluís Domenech i Montaner’s Casa Lleó Morera, Josep Puig i Cadafalch’s Casa Amatller, and Antoni Gaudí’s Casa Batlló. These remarkable buildings were originally designed as homes. When these works were built around the turn of the twentieth century, Passeig de Gràcia was the place to “see and be seen,” where the wealthy elite would meet up and people-watch. Today, these eye-catching architectural works are surrounded by high-end shops.

Field Trips

Aside from touring architectural wonders in the city of Barcelona, the curriculum took us on trips across Catalonia. We toured the cities of Lleida, Tarragona, Olot, and Valencia and explored other marvels like Salvador Dalí’s home in Port Lligat. These study tours included guided walks, guest lectures, and sometimes even bike tours. On each trip, we would all gather for a big group lunch, too. I feel that the immersive nature of these experiences taught much more than I ever would have gleaned from sitting in a classroom.

On our field trips, we were exposed to the works of many Catalan architects like Toni Gironès and RCR Arquitectes. These designers use materials like corten steel, juxtaposed sharply against natural landscape elements, to dramatic effect. Works like theirs emphasize my disagreement with those who think architects cannot design landscapes; while they do focus more on built forms than other landscape designs, they are notable in their minimalism and restraint. The designs are, to me, monuments of respect for the landscape; they aim to emphasize and complement the existing natural forms rather than dominate them.

RCR Arquitectes’ Parc de Pedra Tosca near Olot

Toni Gironès’ Climate Museum in Lleida

In addition to studying these contemporary designs, we also learned about historical Catalan design. We toured centuries-old churches in Tarragona, Valencia, and Lleida, as well as historic gardens in various Catalan cities. On our trips, we learned about not just the contemporary attitude towards design, but also when and how each place we visited was established, and how each location evolved over time. In general, European landscapes contain much deeper recorded history than American ones, so I really appreciated these insights into long-term evolution of cities.

My Studio Project

Clearly, this experience wasn’t like the typical semester of my schooling, where our studio project was the absolute most important thing, the be-all end-all, make-or-break element of our semester. That said, the project we were given was the perfect way to synthesize all our other learning experiences. Our project site layered the historical and contemporary, as a perfect microcosm of the city. At its most basic, our site, which was located in the Barri Gothic, consisted of two public plazas separated by an elevated garden. There is much more than this below the surface (quite literally, but also figuratively). The northernmost plaza on-site hosts a playground frequented by local children, and the southern plaza is the site of a popular mosaic art piece called “El Món Neix en Cada Besada” (“The World Begins with Every Kiss”). The mural is mounted on the wall of the elevated garden that separates the plazas. Both plazas also have areas designated for outdoor eating spaces for restaurants abutting the space.

Northern plaza

Southern plaza

Now, I mysteriously mentioned “much more below the surface.” I also mentioned earlier that most of the Old City of Barcelona is built on top of the ancient city, so you may already be connecting the dots here. That’s right: our project site contains buried artefacts which have been identified and catalogued by archaeologists, buried right beneath the plaza! Not only is there history beneath the site; the northern plaza is also enclosed on one side by a wall built directly around one of the original aqueducts into the ancient city. If you look closely at the photo above, you can see the archways of the aqueduct built into the wall. Our design challenge, then, was to synthesize the temporal layers: the ancient and contemporary, as well as the physical layers: underground artefact level, plaza level, and elevated garden level. It’s a lot to work with, but I’ll show you what I was able to come up with.

My design hinged on the concept of “deconstruction.” This concept is multifaceted; not only did I desire to deconstruct the physical forms found on the site, but I also wanted to deconstruct their connotations and incorporate all the elements into equitable, accessible public space. On the existing site, the elevated garden was privately owned by the building adjacent to it, and was only accessible from inside. Historically, these elevated gardens were established for the wealthy class to have outdoor space that was separated from the public space around it. My design aims to reduce the scope of this private space, and instead mimics its form in multi-level public gardens. As the site is laid out currently, the elevated garden separates the plazas almost completely, leaving only a narrow corridor connecting the spaces on either side. My new design reduces the size of the garden by about half, opening more space up to the public.

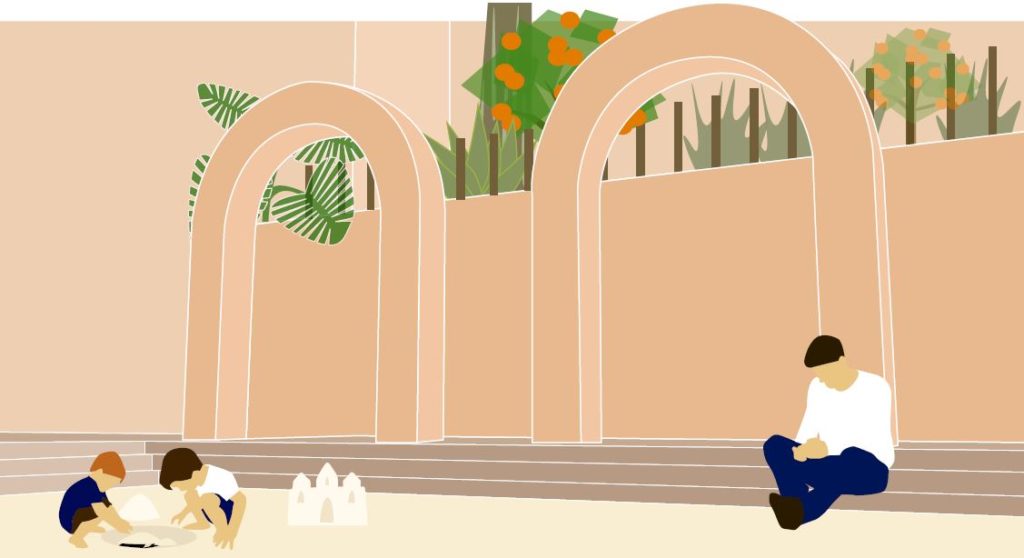

Another goal of my design was to deconstruct the concept of archaeological relics in two ways. First, I proposed a reflective pool beneath the aqueduct wall to emphasize it, and to represent the idea that relics like it are found beneath the surface of the city. I also moved an existing fountain to this space to reflect the historical use of the aqueduct symbolically. Additionally, I proposed a large sandbox, adjacent to the private elevated garden, where children can “dig” for imitation relics directly above where real relics have been identified. The goal of these design elements is to remind Barcelona natives as well as visitors about the origins of the city, buried underground.

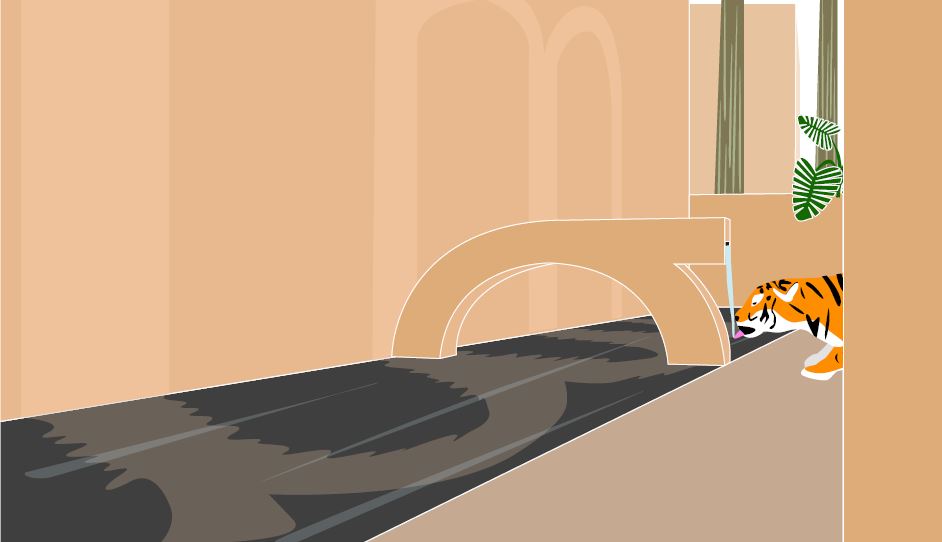

Aqueduct

Sandbox

In addition to these features, my design also includes “deconstructed” arch forms that mimic the arches of the aqueduct. These features divide the different spaces of my design and visually reinforce the concept of deconstruction. My idea was to build gabion arches and fill them with the material removed from the site during construction.

One critique I received of my design during our final review at the end of the program was that I didn’t really do enough to represent “deconstructed” forms in the design. I agree with this assessment; I certainly could have taken the concept further, designing the forms of the gardens and archways to appear as if they are crumbling, or modifying the layout to push the concept further. Of course, any designer worth their salt will tell you that no design is ever REALLY done- there’s always another iteration, another concept, another way to elevate it further. For the duration of the program and how much else I learned and experienced in that time frame, I am very happy with my concept and the level of development I reached.

Overall, I wouldn’t trade the six weeks I spent in Spain for anything. I’ll always remember the people I met, the places I saw, and the lessons I learned (oh, and did I mention the tapas and wine?).

Nice article. I’m glad that the lessons you learned from your early travels with me and mom stayed with you!

Thanks, dad!

Thanks for sharing this experience. My son, Andrew, is going to visit Barcelona Spain for a few weeks this Summer. He is an American student at the University of NC A&T in the landscape architecture program. Your enthusiasm will help with identifying areas to observe as well as appreciation of the rich history. He is not attending the University of Barcelona just doing it on his own. He is interested in the bike tours for guided architectural information. Do you have any contacts for professors or other recommendations while he is in Barcelona?